Fernand Braudel

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF ONE OF THE 20TH CENTURY’S MOST IMPORTANT HISTORIANS

Have you ever wondered how where you live has influenced who you are? Are you a person of the desert, the mountains, the sea? Have you ever questioned the relativity of time or thought of time in terms of its relationship to space? I know I have, and that is why I was so drawn to the famed Annales School historian Fernand Paul Braudel (1902-1985). That and the fact that he is a wonderful storyteller who writes like a poet. I hope that his life and legacy inspire you as they have me.

Fernand Braudel was many things: a teacher, writer, prisoner, husband, and historian. He was also a man who rejected the significance of individual people and events. For more than fifty years he advocated a history “based on a consideration of physical and material constraints, one in which the individual was subsumed by the environment” (Hufton, 209). What would he think of someone writing his story, searching for meaning in the course of his years instead of in the landscapes he inhabited? Many scholars have argued that Braudel was the most significant historian of the 20th century, but how should he be remembered considering his personal opposition to the histories of ‘great men’? This essay examines the influence he had on historiography in the face of that ironic paradox and argues that Braudel’s work galvanized a new geographical, quantitative, and long duration study of history.

BRAUDEL’S LIFE: HOW A RURAL UPBRINGING, TEACHING, AND WAR INFLUENCED BRAUDELIAN THOUGHT

EARLY YEARS

Fernand Paul Braudel was born on August 24, 1902 in Lumeville, a humble village of two hundred people in north eastern France. Raised from an early age by his paternal grandmother, Braudel moved to the outskirts of Paris in 1908. While his father taught in the city, Braudel attended first the Lycee Voltaire and then the Sorbonne, where he got a degree in history “without difficulty, but also without much enjoyment” (Braudel, 449). Braudel noted the instruction of French economic historian Henri Hauser as his one agreeable memory (449) at the Sorbonne. Despite an urban education, he was ultimately more influenced by his earliest years in rural France. Braudel himself credited his upbringing in the countryside—where he experienced first hand the influence of things like crop cycles and weather patterns on the history of his village—as the foundation for much of his geographical historical perspectives later in life.

Algeria and Brazil

“I believe that this spectacle, the Mediterranean as seen from the opposite shore, upside down, had considerable impact on my vision of history.” (Braudel, 450)

Upon graduation, Braudel was assigned a position teaching history in Constantine, Algeria. As a man in his early twenties, Braudel delighted in the city, the Sahara, and in teaching, despite the fact that he was instructing his students “a superficial history of events…of happenings, of politics, of great men” (Braudel, 450). In the summers, when school was not in session, Braudel spent countless hours at the archives working on a thesis surrounding King Phillip II of Spain. Using an old film camera he purchased from an American cameraman, Braudel took upwards of 2,000 photos a day of documents in the archives, inadvertently becoming “the first user of microfilms” (Braudel, 452). This methodology alone changed the way professionals and novices alike do history, but that was only the beginning. His time in Algeria challenged his Eurocentric view of world and opened his eyes to influences on the other side of the Mediterranean.

In 1935 Braudel accepted a teaching position in Sao Paulo, Brazil. For three years he taught a course on the history of civilization and continued his work in the archives. Braudel claimed that from Brazil “he could see the Mediterranean from outside as a whole” while also getting a glimpse into the past by observing the “still surviving forms of social control and modes of exploitation of the land and of the labor force” reminiscent of Medieval Europe (Aymard, 18).

Another significant result of Braudel’s time in Brazil was his introduction to the renowned French historian Lucien Febvre in October of 1937. Both men were on board a ship heading back to Europe, Braudel after teaching in Sao Paulo and Febvre after lecturing in Buenos Aires. After twenty days on the water together, Braudel had become “more than a companion to Lucien Febvre…a little like a son (Braudel, 452). By 1939, after more than a decade in the archives, Braudel was ready to start writing his book on the Mediterranean. But that same year he was called to serve in the French army.

Upon graduation, Braudel was assigned a position teaching history in Constantine, Algeria. As a man in his early twenties, Braudel delighted in the city, the Sahara, and in teaching, despite the fact that he was instructing his students “a superficial history of events…of happenings, of politics, of great men” (Braudel, 450). In the summers, when school was not in session, Braudel spent countless hours at the archives working on a thesis surrounding King Phillip II of Spain. Using an old film camera he purchased from an American cameraman, Braudel took upwards of 2,000 photos a day of documents in the archives, inadvertently becoming “the first user of microfilms” (Braudel, 452). This methodology alone changed the way professionals and novices alike do history, but that was only the beginning. His time in Algeria challenged his Eurocentric view of world and opened his eyes to influences on the other side of the Mediterranean.

In 1935 Braudel accepted a teaching position in Sao Paulo, Brazil. For three years he taught a course on the history of civilization and continued his work in the archives. Braudel claimed that from Brazil “he could see the Mediterranean from outside as a whole” while also getting a glimpse into the past by observing the “still surviving forms of social control and modes of exploitation of the land and of the labor force” reminiscent of Medieval Europe (Aymard, 18).

Another significant result of Braudel’s time in Brazil was his introduction to the renowned French historian Lucien Febvre in October of 1937. Both men were on board a ship heading back to Europe, Braudel after teaching in Sao Paulo and Febvre after lecturing in Buenos Aires. After twenty days on the water together, Braudel had become “more than a companion to Lucien Febvre…a little like a son (Braudel, 452). By 1939, after more than a decade in the archives, Braudel was ready to start writing his book on the Mediterranean. That same year he but was called to serve in the French army.

As a Prisoner of War

From 1940 to 1945, Braudel was a prisoner of war in Nazi Germany. He served at two separate camps—Mainz and Lubeck—finding solace in his writing and in lecturing to fellow prisoners. In his Personal Testimony, Braudel writes of the impact that the burden of time and the times had on his historiographical approach. “My vision of history took on its definitive form without my being entirely aware of it…partly as a direct existential response to the tragic times I was passing through” (Braudel, 454). He was able to survive the horrors of the world around him by denying the importance of individual occurrences in favor of histories written around longer time scales. During this period, Braudel wrote “600,000 words of text from memory” (Hufton, 208) on school notebooks he sent out to Febvre. These would become the draft of his magnum opus, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Time of Phillip II, the book that would define not only the rest of his life but also a shift in 20th century historiography.

Professional Life

The companion article on this site titled “The Annales School” details the influence and implications of these French thinkers; however, the Annales deserves additional attention here for Braudel’s role in its second wave. Upon returning from Brazil, Braudel worked under Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, the original founders of the Annales journal that would inspire the movement. His association with Febvre continued even during his time as a prisoner of war as Braudel sent draft after draft of The Mediterranean to Febvre for safekeeping and review. With the publishing of that work in 1949, Braudel gained widespread notoriety and became the preeminent historian in post-war Europe. Following the death of Febvre in 1956, Braudel took over as director of The Annales. In 1968, “he entrusted his editorial responsibilities to a younger generation of historians…but maintained officially up to his own death the direction” (Aymard, 14) of the Annales.

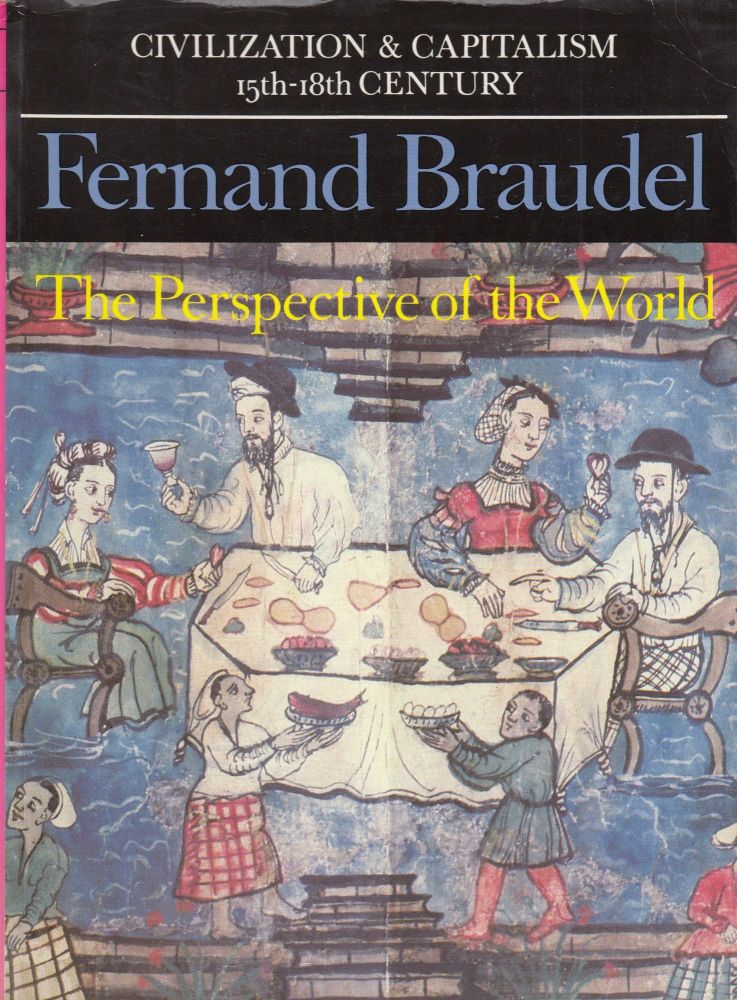

Outside of his time with The Annales, Braudel worked as a professor at the College de France, served as president of the VI section of the Ecole Pratique de Hautes Etudes, and director of the Masion de Sciences de l’Homme (Hufton, 208). All the while, he continued work on a 1966 revision of The Mediterranean as well as a massive new history on Capitalism which he would publish in 1967 under the title Civilization and Capitalism. The Identity of France, published posthumously in 1986, examines the history of Braudel’s motherland and is our final glimpse into the mind of “the greatest and most influential historian of our time” (Hufton, 208).

BRAUDEL’S LEGACY: HOW HIS WORK REPRESENTS A SHIFT IN HISTORIOGRAPHICAL DISCOURSE AND PRODUCTION

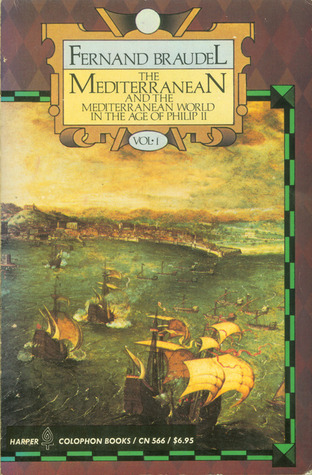

What began as a thesis on the life of King Phillip II of Spain ultimately became a thousand plus page discussion on the history of the Mediterranean using a “tripartite notion on which common time was set on one side” (Hufton, 112) so that the long duration effects of geography, climate, and sociology came to the forefront. The Braudelian perspective of time centered around the idea that all historical events could be examined in distinct time scales: the longue duree, the moyenne duree, and the courte duree. “The longue duree, virtually boundless time, perhaps extending over centuries of common time during which the parameters of human existence were unchanged” (Hufton, 112) was the most influential scale according to Braudel. The moyenne duree relates to “anything in common time perhaps from fifty years to a century” (Hufton, 112) where shifts in trade cycles or urban development are witnessed, for example. Finally, the courte duree refers to “phenomena such as abnormal harvests or short industrial slumps or temporary dislocation which might…be the product of war, occupation, etc.” (Hufton, 112). In the case of The Mediterranean, Braudel tells the story of life during the era of King Phillip from all of these time scales to “teach how, in the lands around the ever-changing and never-changing sea, time and space, history and geography together shaped one coherent past, present, and future” (Marino, 649). His emphasis on the longue duree devalued individual people and events, drawing some criticism from his contemporaries who focused largely on political history and biography.

Capitalism

The Mediterranean

What began as a thesis on the life of King Phillip II of Spain ultimately became a thousand plus page discussion on the history of the Mediterranean. Braudel introduces a three part notion of time in which common time was set on one side so that the long duration effects of geography, climate, and sociology came to the forefront (Hufton, 112).

The Braudelian perspective of time centers around the idea that all historical events could be examined in distinct time scales: the longue duree, the moyenne duree, and the courte duree. “The longue duree, virtually boundless time, perhaps extending over centuries of common time during which the parameters of human existence were unchanged” (Hufton, 112) was the most influential scale according to Braudel. The moyenne duree relates to “anything in common time perhaps from fifty years to a century” (Hufton, 112) where shifts in trade cycles or urban development are witnessed, for example. Finally, the courte duree refers to “phenomena such as abnormal harvests or short industrial slumps or temporary dislocation which might…be the product of war, occupation, etc.” (112).

The Mediterranean, is a story of life during the era of King Phillip from all of these time scales showing “how, in the lands around the ever-changing and never-changing sea, time and space, history and geography together shaped one coherent past, present, and future” (Marino, 649). His emphasis on the longue duree devalued individual people and events, drawing some criticism from his contemporaries, which I will address below. Braudel’s three part temporal structure was a revolutionary idea. At a time when other historians were focusing largely on military campaigns, political successions, and biographies—concerns of the medium and short durations—Braudel offered an epic alternative in the form of a total history of the Mediterranean. His scale, in terms of both time and space, was enormous when compared to his contemporaries. Because of that, he was able to ask different and bigger questions, look for larger trends, and consider the roles that factors like geography and climate play in the shaping of nations and cultures.

The fact that The Mediterranean has been translated into languages as diverse as Chinese, Greek, Hungarian, Dutch, Japanese, and others, is evidence of the widespread interest and appreciation of Braudel’s innovative historiographical approach. A quick search in the library database revealed a diverse variety of scholarship employing his three part temporal approach to history. If you are curious about this type of research and want to know more, check out these publications on Asia, and Africa.

Civilization and Capitalism

Methodology and Writing

Bibliography

Braudel, Fernand. “Personal Testimony.” The Journal of Modern History 44, no. 4 (1972): 448–67.

Caygill, Howard. “Braudel’s Prison Notebooks.” History Workshop Journal, no. 57 (2004): 151–60.

Hanson, Robert C. “Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World, Vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century,” 2005.

Harris, Olivia. “Braudel: Historical Time and the Horror of Discontinuity.” History Workshop Journal, no. 57 (2004): 161–74.

Marino, John A. “The Exile and His Kingdom: The Reception of Braudel’s Mediterranean.” The Journal of Modern History 76, no. 3 (2004): 622–52. https://doi.org/10.1086/425442.

McNeill, William H. “Fernand Braudel, Historian.” The Journal of Modern History 73, no. 1 (2001): 133–46. https://doi.org/10.1086/319882.

“The ‘Annales Movement’ and Its Historiography: A Selective Bibliography.” French Historical Studies 18, no. 1 (1993): 346–55.

Vansina, Jan. “For Oral Tradition (But Not against Braudel).” History in Africa 5 (1978): 351–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171497.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. “Braudel on Capitalism, or Everything Upside Down.” The Journal of Modern History 63, no. 2 (1991): 354–61.

Willis, F. Roy. “The Contribution of the ‘Annales’ School to Agrarian History: A Review Essay.” Agricultural History 52, no. 4 (1978): 538–48.

2878 words. /essays/modernism/fernand-braudel.html