Historical Fiction or History

Why not both?

You’re Sitting in a classroom with yours eyes glazed, teacher droning on with fact after fact as they are force-feeding you history. Sound familiar? Does it really have to be so dry, so…boring? Is there another way to grab our attention and draw us, willingly, into what is really a very exciting world? The answer is yes, the tool…Historical Fiction. More than any other style, Historical Fiction has the ability to take hold of us and draw us into worlds that are exciting and alive.

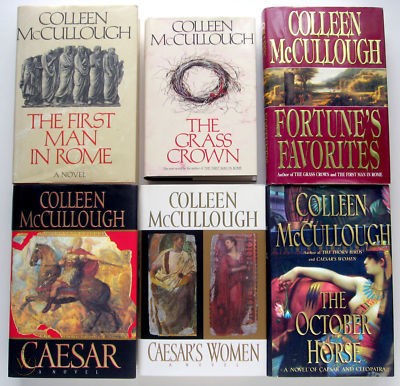

Novels, movies, and television entertain us, helping us escape from the world for a time. They expand our understanding of what is and what can be. They untether us from reality and thrust us into an expanse of diverse and fantastic worlds with engrossing characters. Works like HBOs Rome and Colleen McCullough’s Caesar (part of the Masters of Rome series) can both entertain and educate, in some cases unwittingly, by drawing us into their worlds.

What the Genres?

While there is a vast landscape of literary genres, let’s take a look at three in particular: narrative history, creative history, and historical fiction.

Narrative History or Academic History - This form of historical writing is the one we are most familiar with, having been bored to tears with it throughout those torturous years from elementary through high school. The ‘facts’ of narrative history were beaten into our heads. Rote memorization is the bane of historical narratives, throwing a wet blanket on anything really interesting or exciting in history. This brings back memories of [Ben Stein]’s(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ben_Stein) lecture on the Smoot-Haley Tariff Act in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Minimizing creative license in the narrative, adding elements that cannot be supported by historical sources or the embellishing of fact to enhance the reader’s emotional investment in the narrative, is what had us mainlining No-Doze all through high school. Included in this genre are biographies, memoirs, and documentaries. 12

-

Frederick Jakson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis” gave us a look at the American West and how it evolved. Turner looked to U.S. census data to support his theory on the evolution of the frontier.(book)

-

History Channel’s Modern Marvels provide a light-hearted approach, using the documentary to provide an insiders perspective on the technology that surrounds us. (television)

-

L. Jay Oliva’s Peter the Great is a biography of the first Romanov Tsar of Russia, providing a look at the man’s greatness and his human flaws. (book)

Creative History or Nonfiction - Creative History, or non-fiction, borrows from the academic narrative and interjects elements that may not be supported by historical sources, yet is consistent with the events and larger narrative.3 The information in these books is as accurate and verifiable, but the language and narrative techniques provide readers with a more literary experience and presumably a greater emotional connection with the book’s content. 4

-

Alex Haley’s Roots, adapted for television in the 1970’s, was the first significant work for television to address the origins of African-Americans in North America. haley uses his own ancestry to convey the larger history. (book and television)

-

Nadezhda Durova’s The Cavalry Maiden is an insightful look at an unusual woman who served as a Russian Cavalry Officer in the middle of the 19th century. (book)

Historical Fiction - Now, this is where history started to really ‘grab’ us. Those exciting stories that drew us in and made us feel as though we were living them. Accurate historical settings, characters and larger events, with the addition of elements created by the author that cannot be supported by the historical record, makes historical fiction interesting. It strives “for the story that underlies reality and thus become an imagined reality” 5[^HistFic vs Hist].

-

HBO mini-series Rome is a dense and action-packed presentation of the life of Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar which brings these men and Rome to life, showing their strength and human frailties. (television)

-

Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the tale of the war against Napoleon on the Western Steppe of Russia in 1812 by using fictional characters to advance the large story of war. (book)

-

Gordon Lightfoot’s [“The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centennial_(novel) examines a singular event in maritime history as the tale of strong men and a noble vessel losing in the fight against nature. (song)67

We generally understand that history studies the past,8 but nothing says it needs to be dry and boring (high school flashback). Let’s move forward, and look at how history can be inviting and exciting, and the role historical fiction plays in the adventure.

To simplify matters, and because the lines between them can be indistinct, I’m will simply use ‘historical fiction’ to refer to both historical fiction and creative history. In fairness, historical fiction is part of a literary spectrum ranging from fiction to narrative (academic) history, with several stops along the way. Each of these is part of a spectrum with none holding a fixed position, each arguably blending into the next.

What is historical fiction?

Historical fiction, while based in past events and notable characters, uses fictional interactions and secondary characters to create a vibrant and vivid narrative to engage you, the reader, similar to creative fiction. The American Revolutionary War epic The Patriot uses fictional elements and dialogue to ensnare our interest in the larger story of America’s fight for independence. Benjamin Martin is an amalgam of several historical figures, giving a picture of a man forced into a war of insurgency by the death of his son. This injection of dialogue, minor events, and composite figures, though not supported by historical primary sources, increases our involvement and interest in the story without altering the historical narrative. [^HFwiki]

Lost in Doctrine

Each of us, remembering our high school World History class, knows how dry and uninspiring narrative histories can be. Names, dates, locations, and people are at the very center of what we were all taught history is ‘supposed to be.’ The facts, just the facts, please. No wonder many of us despised these classes, with several falling asleep (no finger pointing here). I point you back to the earlier Ben Stein example.

Without realizing it, we were indoctrinated into the Euro-centric9 and nationalistic histories that colored our understanding of history and the world. Even today, Euro-centrism and nationalism pervade what is taught to children in schools in the western world. Now, what if the method and tools of teaching history were turned upside-down? Enter historical fiction.

Similarities

While narrative history and historical fiction differ, they also have much in common. Each depends on an in-depth knowledge of history’s critical elements: people, places, and period. This knowledge comes from extensive research into each facet of the overriding narrative arc. This is done to convey the most accurate and believable depiction of history. Without the gathering of the credible source material, the author fails to reach us effectively and credibly. It is this common foundation that establishes the value of the content beyond that of mere entertainment.

What is the role of historical fiction?

For centuries we have relied on the traditional ‘narrative’ in the academic world. Whether Greek (Ptolemy, Timaeus), Roman (Tacitus, Livy, Pliny), Christian (Augustine, Eusabius Pamphili, Socrates of Constantinople, Caesar Baronius), or [modern] (Leopold van Ranke, Frederick Jackson Turner, Voltaire), historians have rejected the idea of anything other than the ‘facts for fact’s sake_,’ leaving us with the narrative style we have known throughout our schooling. While the ‘facts’ are central to the very nature of historical studies, there is a lack of emotion and personal investment for us as the readers. Wait, don’t nod off yet!

We can never truly know everything about the past. There is so much that was lost, destroyed, or simply never recorded. this leaves substantial gaps in both the record and our understanding of the past. Historical fiction goes beyond the absolute historical record, interpolating and intuiting the missing dialogues and minor events. It adds a vibrancy—life—that has long been missing from the chronicle. We have all heard tales of Hercules, Apollo, and Icarus. Early civilizations—Greeks, Romans—used myths to inform and teach about their origins and place in the world. This was done to equal effect within Christendom, with the Old and New Testament stories of the Bible, beginning with the creation myth in the “Book of Genesis”. These stories seize our interest because they are exciting. Then, as now, these fictions tell us about who we are and where we come from. These works are, arguably, more fiction than fact, and this is what grabs our attention sucking us into the story. While they are at some level fiction, there is little debate regarding their value in studying of history. 1011

Historical fiction is different. In fact, it is more interesting and possibly more historically accurate, by many accounts, than the Greek, Roman, or Christian mythologies. While interesting, these mythologies provide little historical substance. In this way historical fiction serves a greater purpose to us as readers of history, beyond mere entertainment. We strive for accuracy and detail, which is at the heart of historical fiction, and hunger to understand the moments in between.[^creanon]

Great examples of this are [Colleen McCullough]’s(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colleen_McCullough) Masters of Rome novels and HBOs Rome. These well-research works enliven the world of pre-Christian Rome hurling us into the excitement and intrigue of the Rome of Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar, by using dialogue, personal interactions, and transitional events. While not drawn directly from the historical record, these contrived elements enhance the histories of the primary actors. McCullough’s books tell of the rise to power and rule of Roman men whose names are familiar to us: Gauis Marius (The First man in Rome), Lucius Cornelius Sulla (The Grass Crown), Gaius Julius Caesar (Caesar), and Augustus Caesar. While not academic narratives, these works instill life and vibrancy to history, luring us into their Rome.

Narrative and the ‘Rosenberg Paradox’

In examining the utility of historical fiction in the study of history, we must take a brief look at the primary tool used in history and every other field of endeavor: Narrative. Human history, even our lives today, is wrought with narrative.12 But what is narrative? Can history or anything else, for that matter, be communicated without it?

Within professional historical studies…the narrative has been viewed for the most part neither as a product of a theory nor as the basis for a method, but rather as a form of discourse which may or may not be used for the repre- sentation of historical events, depending upon whether the primary aim is to describe a situation, analyze an historical process, or tell a story.[White2]

Narrative is that process of conveying information through a story. With the exception of numerical data, everything we say and write is part of a narrative.[White1] We are story tellers at heart, and it is through stories that we add meaning to events, and data. Though argued by many, including Michel Foucault, Jean-Francios Lyotard, and Alun Munslow, it is Alex Rosenberg (a Professor of Philosophy and author of two historical novels) who makes the most direct assault on narrative’s utility painting a bold target on historians use of the tool.

Rosenberg claims that narrative clouds our understanding of history, tainting it. Though deeply ingrained in who we are as human beings,12 narrative is something that we must excise from how history is told, adopting the more sterile scientific method to communicate the past 13.

Ironically, the very vehicle they wish to cast aside is precisely the tool they use communicate information and enhance our understanding. 12 Rosenberg admits that he, as much as anyone, is a “victim of narrative.” Like Rosenberg, historians, philosophers, doctors, accountants, and scientists are dependent on narrative to share their ideas. Without narrative information loses meaning and falls on deaf ears. [White1] Therein lies the paradox of Rosenberg’s argument: with narrative information (history) is tainted; without it there is no meaning, it devolves to data points.13

Hayden White, a classically trained medievalist and narrativist14, contended that ‘“The Burden of History” interpreted history as storytelling, contending that without attending to the craft of writing the discipline would fail to keep up intellectually with other scholarly fields.’[^Stoval1] And so, “narrative “is simply there like life itself. . international, transhistorical, transcultural.”[Barthes1]

A historical narrative is thus necessarily a mixture of adequately and inadequately explained events, a congeries of established and inferred facts, at once a representation that is an interpretation and an interpretation that passes for an explanation of the whole process mirrored in the narrative. 15

Truth, objectivity and fiction?

Before I wade into the questions of truth and objectivity—and I don’t want to get any more than ankle deep in these two areas—there is something that we must all agree on: We are all human. As humans the world around us is subject to interpretation, each person having their own understanding and view of the world around them. The same premise holds true for truth. There are very few “absolute truths” in the world, death and taxes being the first that come to mind.

Truth is as individual as each of us. Sure, we can look at historical documents, those written by those who observed and lived in a particular time and place, thinking they are representative of the actual historical event. But there were tens, or hundreds, or thousands of people present and only a handful recorded the occurrence, and fewer still of those accounts survive the passage of time. In reviewing these personal accounts, we are getting a single human perspective and assessing its contents as “truth,” until we discover another record that either affirms or contradicts the one we are most familiar with.

This leads to the second half of the fallacy: objectivity. If we had accounts of a single event from any number of witnesses, each of whom diligently recorded the event in great detail, there be as many variations in the accounts as there were people present. Which do we hold as accurate? Which are the most ‘objective?’ Objectivity is, like truth, a very difficult concept to assess. To claim objectivity means to deny all the we are and that we have experience. Life shapes us, gradually building unseen biases. The existence of biases means there can be no absolute objectivity.

Clearly, we can’t accept these works of historical fiction as historical ‘truth.’ With the addition of fictional elements, we have to divine fact from ‘fantasy’. Even so, the factual portions of these works are enhanced by the inclusion of the fictional elements. Provided we understand and recognize the difference between the history and the fiction, historical fiction can present a more significant opportunity to grasp and become involved in the story that narrative accounts are unable to accomplish.

A place for historical fiction in the study of history?

By its very nature, historical fiction is part of the study of history. Building upon subject matter research, these works extend the reach of traditional narrative histories. Authors of the historical fiction are, to varying degrees, committed to building a world based on factual, credible evidence to construct a firm historical foundation for their works. Without this foundation, the author and work are lacking in credibility and cast us into a world of fantasy. While still engaging, it fails to enhance our understanding of the past and draw us into a more in-depth search into past events, places, and personalities.

Expanding interest in history?

The author’s passion for the subject and their dedication to research and accuracy of the presentation carries over to us, the audience. These elements enhance the study with the development of dialogue and characters we are unable to reconstruct from historical sources. They add to our ability to visualize the people, places, and events in a historical context. Historical fiction gains our emotional investment by creating an active and engaging environment, acting as a tool to increase our interest in the historical topic the author is presenting.

Sign on the Dotted line?

Though interspersed with fictional elements, these works increase our personal involvement in history, driving us to read and investigate the subject more deeply through more traditional academic sources. Reaching into the primary source material, these inquiries into the past increase our interest and involvement in history. Integrating works of historical fiction (and creative history) into the academic environment provides a means of drawing more students into the study of history.

In Closing

Before anyone says that my purpose here is to move anyone away from the study of history into an exclusive reading of historical fiction, nothing could be further from the truth. The purpose here is to expand your reading library to include works of historical fiction to supplement the contribution of writers of narrative histories. Does anyone watch only one genre of movie or play only one game? There is little to be gained in living life like this, except maybe a sense of ennui that comes from the lack of variety or diversity in these lives. Reading historical fiction from a comparative perspective adds to the richness of other narratives and styles.

The study of history can be quite dry or very engaging. Looking back on the past not only tells us about where we came from but can inform us about where we are going. It helps us to understand ourselves and those around us. The study of history builds skills that serve us in virtually every field of endeavor. Through research, organization, language, and argumentative writing, we are better prepared to face the challenges of the ‘real world.’ But is something missing?

With the addition of well-researched historical fiction to the study of history, we are adding a creative spark that may well be lacking in the field. Creativity manifests itself in many ways, such as invention and expression. Creativity nourishes, expanding our visions, and drawing us closer to who we are. Should we now deny the very essence of creativity in the study of history? How can we deny our nature as an imaginative and resourceful species?

| [^creanon]: “Historical Narratives | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://creativenonfiction.org/historical-narratives. |

References

“20 Quotes on Writing From Famous Authors.” ThoughtCo.com. Accessed November 5, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-writing-1689236.

“Academic Writing.” Wikipedia, November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Academic_writing&oldid=924805383.

“Act Of Creation Quotes (5 Quotes).” Accessed November 6, 2019. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/act-of-creation.

“Alternate History.” Wikipedia, November 4, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alternate_history&oldid=924519761.

“Creative Nonfiction - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_nonfiction.

“Historical Fiction.” Wikipedia, November 5, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Historical_fiction&oldid=924773655.

| “Historical Narratives | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://creativenonfiction.org/historical-narratives. |

“Is Historical Fiction a Form of Non-Fiction? - Delphinium Books.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.delphiniumbooks.com/is-historical-fiction-a-form-of-non-fiction/.

“List of Historical Novels.” Wikipedia, October 15, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_historical_novels&oldid=921389179.

“Narrative - Dictionary Definition.” Vocabulary.com. Accessed November 13, 2019. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/narrative.

“Narrative History.” Wikipedia, September 21, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Narrative_history&oldid=860511626.

“Narrative History - Wikipedia.” Accessed November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrative_history.

“Narrative Nonfiction vs Historical Fiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://www.childrencomefirst.com/narrativenonfiction-historicalfiction.shtml.

“Nonfiction vs. Creative Nonfiction vs. Historical Fiction – Donna Janell Bowman.” Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.donnajanellbowman.com/2010/08/25/nonfiction-vs-creative-nonfiction-vs-historical-fiction/.

| “What Is Creative Nonfiction? | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed November 7, 2019. https://www.creativenonfiction.org/online-reading/what-creative-nonfiction. |

“What Is the Relationship between History and Historical Fiction? - OpenLearn - Open University.” Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/creative-writing/what-the-relationship-between-history-and-historical-fiction.

Barthes, Roland. “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives,” Music, Image, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York, 1977), p. 79

Bowman, Donna Janell. “Nonfiction vs. Creative Nonfiction vs. Historical Fiction.” Donna Janell Bowman. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.donnajanellbowman.com/2010/08/25/nonfiction-vs-creative-nonfiction-vs-historical-fiction/.

Huskinson, Janet. “Looking for Culture, Identity and Power,” n.d., 25. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/613847/mod_resource/content/1/aa309_1_reading_001.pdf.

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. London; New York: Routledge, 2003.

McCullough, Colleen. Caesar. London : Head of Zeus, 2014.

———. The First Man in Rome. New York : Morrow, 1990.

———. The Grass Crown. New York : W. Morrow, 1991.

Mickel, Emanuel J. “Fictional History and Historical Fiction.” Romance Philology 66, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 57–96. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RPH.5.100799.

O’Grady, Megan. “Why Are We Living in a Golden Age of Historical Fiction?” The New York Times, May 7, 2019, sec. T Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/07/t-magazine/historical-fiction-books.html.

Paul, Herman. Hayden White. (London, Polity Press, 2011), 10.

Rosenberg, Alex. “Why Most Narrative History Is Wrong.” Salon, October 7, 2019. https://www.salon.com/2018/10/07/why-most-narrative-history-is-wrong/.

Sanger, Thomas. “Historical Fiction vs Narrative Nonfiction: What’s in a Genre?” Thomas Sanger. Accessed October 23, 2019. http://thomascsanger.com/thomas-c-sanger/historical-fiction-vs-narrative-non-fiction-whats-genre/.

Stovall, Tyler. “In Memoriam: Hayden V. White (1928-2018)” Perspectives on History, September 2018. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/september-2018/hayden-v-white-(1928%E2%80%932018).

Tod, M. K. “7 Elements of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, March 24, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/03/24/7-elements-of-historical-fiction/.

———. “10 Thoughts on the Purpose of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, April 14, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/04/14/10-thoughts-on-the-purpose-of-historical-fiction/.

Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace. Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2010.

Vallar, Cindy. “Historical Fiction vs. History.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.cindyvallar.com/histfic.html.

White, Hayden. “Interpretation in History.” New Literary History, vol 4 no 2 (Winter 1973), 281-314. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/468478.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_SYC-4802%2Fcontrol&refreqid=search%3A041dff955170a1501e014044b99b2b90.

———. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in the Nineteenth-century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1975.

———. “The Question of Narrative in Contemporary Historical Theory.” History and Theory, vol 23 no 1 (February 1984): 1-33. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2504969?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

———. “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality.” Critical Inquiry vol 7 no 1 (Autumn 1908), 5-27. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1343174.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_SYC-4802%2Fcontrol&refreqid=search%3A041dff955170a1501e014044b99b2b90.

-

“Narrative History.” Wikipedia, September 21, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Narrative_history&oldid=860511626. ↩

-

“Academic Writing.” Wikipedia, November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Academic_writing&oldid=924805383. ↩

-

“Creative Nonfiction - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_nonfiction. ↩

-

Sanger, Thomas. “Historical Fiction vs Narrative Nonfiction: What’s in a Genre?” Thomas Sanger. Accessed October 23, 2019. http://thomascsanger.com/thomas-c-sanger/historical-fiction-vs-narrative-non-fiction-whats-genre/. ↩

-

“Historical Fiction.” Wikipedia, November 5, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Historical_fiction&oldid=924773655. ↩

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9vST6hVRj2A ↩

-

https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/gordonlightfoot/thewreckoftheedmundfitzgerald.html ↩

-

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. London; New York: Routledge, 2003. ↩

-

https://unm-historiography.github.io/intro-guide/essays/thematic/eurocentrism ↩

-

Tod, M. K. “10 Thoughts on the Purpose of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, April 14, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/04/14/10-thoughts-on-the-purpose-of-historical-fiction/. ↩

-

“Is Historical Fiction a Form of Non-Fiction? - Delphinium Books.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.delphiniumbooks.com/is-historical-fiction-a-form-of-non-fiction/. ↩

-

White, Hayden. “The Question of Narrative in Contemporary Historical Theory.” History and Theory, vol 23 no 1 (February 1984): 1. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2504969?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Rosenberg, Alex. “Why Most Narrative History Is Wrong.” Salon, October 7, 2019. https://www.salon.com/2018/10/07/why-most-narrative-history-is-wrong/. ↩ ↩2

-

Paul, Herman. Hayden White. (London, Polity Press, 2011), 10. ↩

-

White, Hayden. “Interpretation in History.” New Literary History, vol 4 no 2 (Winter 1973), 281. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/468478.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_SYC-4802%2Fcontrol&refreqid=search%3A041dff955170a1501e014044b99b2b90. ↩