Time in History

In historical practices throughout history from the ancient greeks to Christians, there are different perceptions of time at work. These perceptions of time are influenced by things like religion, politics, or seasons. Perceptions of time have been greatly influenced by beliefs in the Golden Age. Then there is the topic of the past, present, and future and how different civilizations perceived each one and the value in which they held each term. These things all converge and give us different temporal dialects. Perceptions of time matter because they influence how we see the future or how we value the future.

Cyclical History

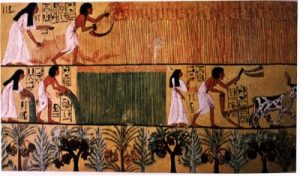

Beginning in ancient times, the significant empires throughout the period had a mostly cyclical view of history influenced by different aspects of culture. Before we go into the different civilizations that used cyclical history, we need to define cyclical history. Cyclical history is the notion that the nature of history is repeating in a cyclical pattern. An example of a cyclical would be the repeating of the seasons (spring, summer, fall, and winter). The seasons very much influenced Egyptians perceptions of history. Their cyclical view revolved around natural cycles like that of seasons very much in part to the importance of the Nile River and knowing at what time it would flood. Time was therefore determined or perceived as, according to G.J. Whitrow in Time in History, “a succession of reoccurring phases” (Whitrow 25). In the Persian era,Zoroastrianism emerged.

Zoroastrianism was the first religion to be monotheistic. Monotheism, as we will see later on, plays a big role in a culture or society’s perception of time. In the case of the Zoroastrian religion, time was the creator; it was the supreme being. There were two perceptions of time that were simultaneous. The First being Zurvan akaran( infinite time) “progenitor of the universe and of the spirits of good and evil” (Whitrow 35). The second is Zurvan daregho- chvadhata (finite time) that brings death and decay this time can be understood as the time that humans follow while Infinite time is the time of the Gods. One is not without the other, “finite-time came into existence out of infinite time. It goes through a cycle of changes until it finally returns to its original state” (Whitrow 35).

According to Arnaldo Momigliano in Time in Ancient Historiography, Thucydides is whom we should attribute the cyclical view of history “(Momigliano 11). Thucydides (460-400) was a Greek historian who wrote about the Peloponnesian war. Thucydides was under the belief that “there will be future events either identical or similar” to the ones he narrated (Momigliano 11). Nemesius, Bishop of Emesa, was under the belief that people would live the same life with the same people again and again. Nemesius stating that both Socrates and Plato would be once again (Whitrow 43). It is essential to realize that not every Greek intellectual was under the belief that history was cyclical. Some believed that only politics or changing of political climate was cyclical, not history as a whole.

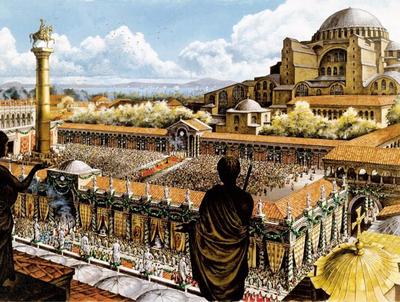

The Roman empire believed that they were timeless, believing that their empire was the peak of perfection. Although they felt that they were at a sort of end because of the perfection in which the Romans believed they had reached, they still had a cyclical view of history. This changed with the Roman emperor Constantine (272-337), who in the year 313 with the Edict of Milan put into law religious tolerance.

Linear History

As Christianity took over the Roman empire, there was a paradigm shift from a cyclical nature of history to a linear nature of history. A paradigm shift is a major shift in thinking or practice. Linear history is history that follows a linear path and does not repeat; it has a beginning and an end. The linear nature of history quickly became the way in which intellectuals wrote history; it began to permeate all scholarship in the western world. A famous advocate of linear history was St. Augustine of Hippo. St. Augustine (354-430) was a Christian theologian who wrote many famous works, two of them being the City of God and [The Confessions](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confessions_(Augustine). In his writings, “he rejected the idea of cosmic and historical cycles endlessly recurring” (Lemon 91). In his Confessions, more specifically, we see the way in which Augustine perceived time. Carlo Marcaccini writes about Augustine stating that

“Time is circumscribed; it has a beginning and an end, and for this reason it is also transitory, not continuing for all eternity. These characteristics emerge in opposition to the infinite, immobile and indeed eternal nature of God. It is certainly a paradox that it is the ontological ineffability of time its not-being placed before the divine being that allows us to conceive and define it; but it is precisely within this framework that Augustine slowly evolves in his pursuit of the truth”(215).

Golden Ages

The Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians were all under the belief that time began with a Golden age. The Golden age was when God or Gods and man were close to one another. Until a time where something happened and disrupted the relationship between the two, and they were separated. In this form or perception of time, humans are on a decline having started from the top and now falling into a more primitive state of mind and society.

In a different perception of time, humans at the beginning were primitive beast but are on the incline as they acquire more knowledge through time. This can be seen especially in that of Judaism and Christianity. While man did start in a type of Golden Age in the Garden of Eden, humans since the fall are working their ways towards salvation. Cyclical history requires a dualism or polytheistic view or substantial importance on politics. While linear history is focused on the one, god one path for “faith expressed itself, according to Eliade, in a linear view of history” (Olsen 17). While it was unintentional linear history is what became the way in which to write history. To put it in more perspective Whitrow states that

“Whereas for most Greeks and Romans, whether they believed in cycles or not, the dominant aspects of time were the present and the past, Christianity directed man’s attention to the future. Pg. 64-65).

Time tells us a lot about a culture and or civilization. Looking at polytheistic groups like that of the Egyptians, we can descreen they had a more cyclical view of time. Those who were monotheistic, therefore, had a linear view of time. Understanding what time says about a culture or society is vital to histography. It can be used as a method to uncover some biased or inclination of one’s view of themselves in time. Cycles may work for one type of history like that of political or economical but not for things like religion; Cairns puts this into perspective saying “there are cyclical patterns he admits in the rise and fall of great civilizations; nevertheless there has been linear progress on the whole in religion “(Cairns 279).

Time of the Scholar vs. Time of the Ordinary Man

Historically, the overall written account of history has come from the upper class like that of philosophers, scholars, and from institutions like that of the church. For the majority of academic scholarship, history has been written by very few. This is important, especially when it comes to perceptions of time and historical progress. For academic scholarship, time is linear because of non-repeating events in the overall historical narrative. For the ordinary man, however, he may feel that it is cyclical because of the life that he or she lives. For people or cultures that rely or have relied on farming to live, they are often under a cyclical view of time. Momigliano says that “there is no reason to consider Plato’s thoughts about time as typical of the ordinary Greek man” (Time in Ancient Historiography 8). When studying history, it is for this reason that we need to be aware of the different types of time that people are writing history. While some are writing under the impression that there is a repetition, others are writing under the impression that there is not. Another impression that time can have is when it comes to the past, present, and future.

Past, Present, Future

The Greeks, Romans, and Jews put different emphasis on the past, present, and future. The Greek’s concern lay more in the past because of the lack of historical account that Greek historians had of past historical events. The Greeks were in a sort of race against time as historical evidence, and sources disappeared due to decay. In Essays in Ancient and Modern Historiography, Arnoldo Momigliano states that “there was more concern with the future among Roman historians, and it expressed itself in anxiety about the Roman empire.” (Essay in Historiography 193). The future of the empire was the main focus of Roman intellectuals. The thought of Rome eternal and the state of politics influenced the emphasis they put on the future. In Roman historical writing and study, one of the objectives was to determine the future.

For the Jews as well as the Christians, time was about the present and the future. God was in the present, but he was also in the future when it was time for salvation. There was not worry about the past more of an understanding of the present and the future in terms of religion. In modern historiographical study, the past, present, and future are not clear cut. Today history and the understanding of history is about the past. However, understanding where people were coming from or what they valued, whether that be the past, present, or future, can help us better understand the motive behind historical writings. The problem is that “in ordinary oral or written communication, the reference either to past or to the future can be left to the understanding or imagination of the recipient” (Momigliano Time in Ancient Historiography 6). Time is up for interpretation in history, especially when the sources are old. Historiographical interpretation of time can lead to a cyclical or linear progression of historical events.

Teaching Linear History

Today a linear view of history is taught in schools. In school, there is an overall incline view of the direction in which history is moving, not one of dissension when teaching the history of civilization. Teaching the linear path of history implies that there will be an eventual incline or decline of historical progress; therefore, this may or may not create a biased. The Roman empire had a cyclical path of time. This greatly influenced their opinion of themselves and their empire, giving them a sort of evidence that they were at the peak of perfection the Rome eternal. Time can be used as a method to write history in a particular way or to teach history in a certain way. When talking about the Mayans or the ancient Greeks, there are different conceptualizations of time that need to be accounted for in order to understand their history and the importance that they placed in history. The multiple times at work in historical narrative teach about the beliefs of cultures.

Questions we need to Answer

Some questions and answers need to be considered when thinking about time in history in general.

How do we reconcile multiple perceptions of time when writing about history? When studying history, especially Zoroastrian, Greek, or Roman, we need to be aware of the cyclical nature of the history that was written by these groups. Especially today, since the nature of history is taught as being linear, this means that “it is not enough to simply eliminate a narrativeís chronology, but one must attempt to understand temporal dialectics” (Marcaccini 218). Understanding how these temporal dialects influence the way in which history is portrayed is a way in which we can reconcile the two and have a better understanding of how history was written in ancient times into the present times.

Are conceptions of time an integral part of a culture’s history? Yes, they are. Looking at the way one culture looks at time can tell us important aspects of what they believe regarding religion. Both the Greeks and Romans were polytheistic, and there cyclical view of history reflects this. Jewish and Christian were monotheistic, and their view of time was strictly linear. Going back to Egyptians or groups that relied heavily on farming time was based on the cyclical pattern of the season. We can infer different characteristics of a society by the way they write history.

Have perceptions of history changed especially with the advancement of technology? Indeed, the advancement of technology has changed perceptions of time. Having thousands of years of historical information in one place has allowed historians to view the linear path of history and some of its cyclical patterns. Both linear and cyclical patterns are at play in history. In History as a giant data set: how analyzing the past could help save the future Laura Spiney writes about how, through data, we can see the circular nature of historical events that could help us prepare for the future. A data set of history could predict things like the time of revolution or patterns of things like war. Using Quantitative history resources can help improve predictions because of its “reliance on numerical data” (Green 141).

Understanding temporal dialectics and perceptions of time help people to understand better the beliefs of a culture and their perception of where they were in time. Rome felt that they were at the end of time in one way or another because they were perfect; they believed humanity started at the bottom and then progressed at an incline until it reached the top, which was them. Although time is taught as linear today, understanding both linear and cyclical is critical as there are cyclical patterns in history. With data, we can gauge when a revolution is on the rise or the cycle of empire from the beginning to the end.

Bibliography

Cairns, Grace E. Philosophies of History; Meeting of East and West in Cycle-Pattern Theories of History. New York, Philosophical Library [1962], 1962.

Green, Anna, and Kathleen Troup. “Quantitative History.” In The Houses of History : A Critical Reader in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. New York : New York University Press, 1999., 1999.

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. Routledge, 2003.

Marcaccini, Carlo. “Time and Truth in Thucydides.” Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades 19, no. 37 (2017): 213–34. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28250843012.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. Essays in Ancient and Modern Historiography. Middletown, Conn. : Wesleyan University Press, 1977., 1977.

Momigliano, Arnaldo. “Time in Ancient Historiography.” History and Theory 6 (1966): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504249.

Olsen, Glenn W. Supper at Emmaus. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2016. http://libproxy.unm.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1429297&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Spinney, Laura. “History as a Giant Data Set: How Analysing the Past Could Help Save the Future.” The Guardian, November 12, 2019, sec. Technology. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/nov/12/history-as-a-giant-data-set-how-analysing-the-past-could-help-save-the-future.

Whitrow, G. J. Time in History : The Evolution of Our General Awareness of Time and Temporal Perspective. Oxford [Oxfordshire] ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1988., 1988.

2714 words. /essays/thematic/time-in-history.html