The Study of Witches

Why Witches?

In this essay, I will be looking into the study of witches starting at the turn of the 20th century to the present. I will be looking at specific historians and the viewpoints most groups took while approaching the subject of the trials. As well I am limiting myself to Northern European and US historians who look at sources from the 16th and 17th centuries as a way to understand a specific set of mindsets towards witches. As most of our history falls into a western frame, I believed it would be easiest to understand the difference in the economic and gendered viewpoints of witch historiography in the regions of France, England, Germany, Spain, the US, and some surrounding regions as they arise within this framework.

Introduction

Witches have been a mainstream halloween costume depicting anything from an old hag to a young and promiscuous women. These stereotypes are not separated in an academic setting, rather further defined and reasoned with. Raising questions among historians and other philosophers as to why witches are important to a society in the first place? The witch craze of the 16th and 17th centuries stigmatized being unmarried, a sole heirace, an old Hag, essentially any women who could feel powerful for any reason. There are other aspects of society that are affected by the mass amount of executions and trails and general accustasations. These aspects are what historians seek to understand and give further reason towards. The Salem witch trials were just one of many places heavily corrupted by the ease of accusing a woman of tempering with livestock, human life, and other forms of wealth and virtue. The trials that took place in England and Germany were horrific in the amount of women who died merely because someone had a grudge or reason for executing their neighbor.

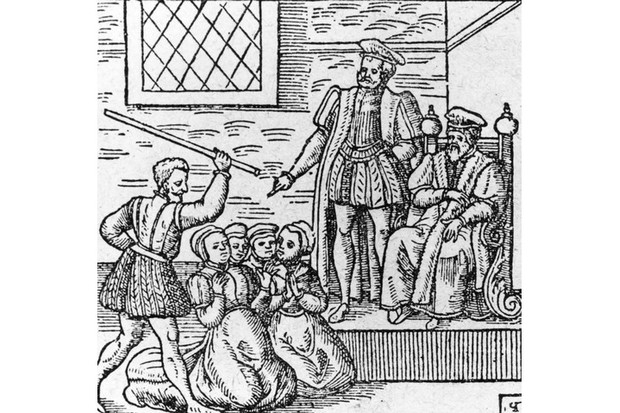

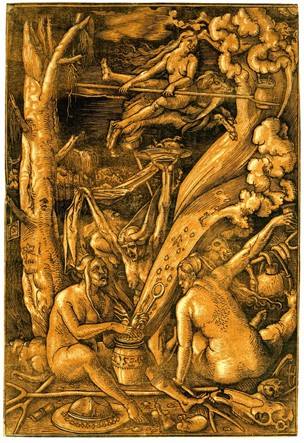

witches_baldung.jpg https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1333755&partId=1

witches_baldung_paper.jpg https://museumofwitchcraftandmagic.co.uk/object/witch-picture-57/

Not using directly femine pronouns or language to assert the bias of the trials in his description, Heningsen looked at a more religious and economical standpoint.

The Historians of Witches

- Christina Larner: Scottish witchcraft historian and a professor of Sociology at The University of Glasgow. She is credited with calling the “witch-hunts” “women hunts” in her research but not fully concluding the actual role of gender in the overall hunts. Her three books are A Sourebok of Scottish Witchcraft (1977) , Enemies of God (1981) , and Witchcraft and Religion (1984). The influence the post modern idea of thought is exemplified in Larner’s work. She is an early female historian who dedicated her historical work to a sociological phenomenon, the witch hunts. Her findings followed the many trends of economics but was always aware of the potential impact being a women would have had on the people in her chosen timelines. As women

The main method used in the historiography of witches is from the postmodern perspective. The idea that the “witch hunts” were actually “women hunts” (Christina Larner) giving this seeming economic study a more gendered face is still not fully recognized but debated and questioned. Joseph Hansen, one of the first witch historians from Germany, published his book Zauberwahn, Inquisition und Hexenprozess im Mittelalter und die Entstehung der grossen Hexenverfolgung (Magical Illusion, Inquisition, and Witch Trials in the Middle Ages, and the Formation of the Larger Persecution of Witches) in 1900, mentioning but not focusing on the fact that mainly women were persecuted. Many historians who looked at the hunts later mostly looked at the economic and socio economic value in the hunts as this is what the modernist historians did. Trial records, execution records, and other quantitative records were used to understand how the trials were used as an economic.

Historians such as Keith Thomas, Alan Macfarlane, and Gustav Henningsen looked at the folklore believes in society that led to the witch hunts. The dynamic between the “male-dominated official culture and a female-dominated family and folk culture” (International Trends) were not their focus when using more official based documents to extract folklore representations. Henningsen also describes accused witches as either the “weakest members of the community, including beggars, cripples, widows, the very old and orphans” or “those who had rejected the moral order of society: fawning, envious, thieving, aggressive, spiteful, promiscuous and odd people,”

764 words. /essays/thematic/women-gender/the-study-of-witches.html