Historiography of Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth I of England was one of the most idealized and revered monarchs in European history. Ruling for 44 years, from 1558 to her death in 1603, she still stays on the list of top ten longest-ruling monarchs of the United Kingdom. Perhaps most impressively, she managed to accomplish this despite the fact that she was a woman. But how did different historians throughout time think of her?

The answer is, it depends. Different historians throughout time have had different standards for writing history. Historiography is, among other things, the study of these historians, and of the writing of history itself.

In history, there has been very little attention paid to women before the modern era. There are, however, exceptions, a key one being the history of female rulers, and other female members of royal families. The treatment of Queens like Elizabeth I, Victoria, Isabella I of Castille, and Catherine the Great serve as indicators and influencers for the overall view of women in the public reckoning. These women also serve as examples of well-covered historical material, which makes it easier to compare the styles and structures of the historians who wrote about them.

Queens, and other high-ranking women, were written about by male historians before the rise of post modernism in Historiography. This is what makes them interesting characters we can use to observe the general opinions towards women during the era in which historians wrote about them, as well as general barometers for the methodologies of those historians. Here we will look at three different biographies of Elizabeth I and compare the methodology and philosophical leanings of the authors who wrote them.

Each biography has a structure representative of the historical methodologies and philosophies of the era in which they were written. They each also have a common story, regardless of the focus of the biography itself: that of Elizabeth’s favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Favourites, as they are often called in reference to Elizabeth and other monarchs, are typically romantic interests of the King or Queen, given priority in their opinions on matters of state and other governmental decisions. The different approaches to the relationship between Elizabeth and Dudley serve to further articulate the biographers’ own eras of historiography, and for this reason we will examine them as well.

Early Histories

A Post-Renaissance, Pre-Enlightenment Elizabeth

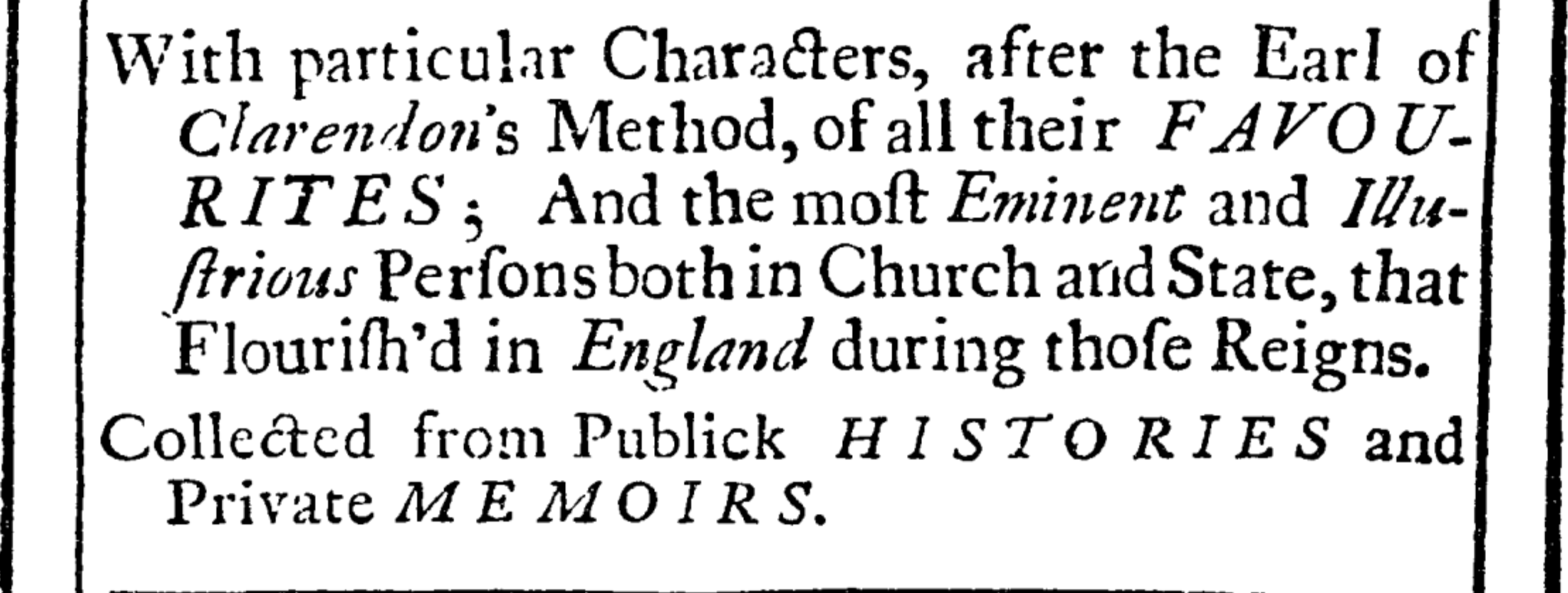

The oldest biography we’ll look at is Observations and remarks upon the lives and reigns of King Henry VIII. King Edward VI. Queen Mary I. Queen Elizabeth, and King James I., written in 1712. It was written just before, or at most during the very beginning of, the Enlightenment Era, which was significant to historiography because of its emphasis towards progress and idealism, described in more detail here. However, Renaissance historians were more influenced by religion than their Enlightenment counterparts, but did subscribe to the idea that tangible human causes were at work in the story of history.

The structure of this work is not recognizable to modern historians. There are no sources cited, just a mention of their existence at the beginning:

The language within the work is also different from a modern biography. Although Elizabeth’s chapter begins in a traditional way, it takes a turn. The author begins with her ancestry, her childhood, and her claim to the throne. They then describe her conflict with her sister and predecessor, Queen Mary I, culminating in her coronation at the age of 26. It is here that we can again see the difference with which historians approached their works:

…Fortune finding, that her time of Servitude Expir’d at her Sister’s death, she put a Scepter in her Hand, and a Crown upon her Head, as a Reward of her Patience. This happen’d in the 26th year of her Age, a time in which with respect to her External Endowments she was full Blown, and for Internal Qualifications, she was grown Ripe, and Season’d with Adversity…

There are two things here to note. The first is the heavily biased nature of the document: rather than say Elizabeth became Queen at her sister’s death, the historian chooses a heavily narrative style characteristic of these early histories. This means the historian is choosing to tell a story, like one we could read in a novel, above listing facts one at a time.

The second object of interest is the particular attention paid to her physical features, which continue at length in this chapter. All of the male monarchs in this book have very different treatments. While the description of Henry VIII has no mention of his physical attributes, that of Edward only mentions his eyes containing a starry quality. Mary I, comparitively, also has a long physical description like that given to her younger sister Elizabeth.

This indicates a priority placed in the culture at the time on the physical maturity of a woman and the emphasis of beauty in their overall value. This work continues to approach Elizabeth in a markedly different way than male monarchs, spending more time on her appearance and personality than her governmental decisions or her contributions to the Reformation period.

However, the section regarding Elizabeth’s favorites is very similar to the rest. As stated above, Robert Dudley of Leicester was of particular interest to Queen Elizabeth. Here is what this author has to say about him:

“I cannot agree with the common received opinion that the Earl of Leicester was Absolute and Superior to all others in her Favour; for tho’ I am somewhat short in the Knowledge of the times, I am well assured, from very good Hands, that the contrary was apparent…” (218).

They go on to describe that Dudley must not have had particular control over Elizabeth, indicating that she could not have, therefore, held him in her favor. This indicates how the author feels about the strength of a woman’s character, even that of a monarch. But why is this important? Because this indicates how the author feels about women.

If Elizabeth, who remained unmarried had shown particular favor towards a man, it would negate her claims to power, which would not be the case for a man. It again showcases the narrative quality of historical accounts at the time. This style is the same from monarch to monarch in this book. For example, the treatment of Edward VI’s premature death is told in the same way:

“And when he died, they said, That the Sins of England must needs be very great, that had provok’d God to deprive them of such a Prince, under whose Government they were like to enjoy Blessed times” (108).

An Early Rankean Elizabeth

The second biography, written in 1896, is simply titled Queen Elizabeth, by J.E. Neale. This era places it firmly after the introduction of Ranke’s philosophy of history, which emphasized objectivity, peer review, and a standardized methodology still recognizable to modern readers.

This is, in some ways, a Rankean approach to Elizabeth’s life, with chapters in chronological order addressing different aspects of her reign. However, we can see here that Rankean historiography did not have complete control. In this book, there are no references, and no bibliography. However, the author directly addresses this, saying the book is not meant for historical research purposes. The lack of references indicates the perspective of the time, which was only beginning to place high value on more modern historical methodology, and the explanation shows that this value was, in fact, existant.

In terms of its approach to Robert Dudley, the book has a different perspective than the first source:

“It is not strange that a lively young woman of twenty-five, unmarried, and living, so to speak, as the hostess of an exclusive men’s club- the Court- should delight in the company of one of its most fascinating members. Nor is it strange that she felt an emotional response to his manhood” (77).

Here we can, again, see two phenomena at play: that of historical thinking and of the view of women historically. The former is a clearly biased statement, one of opinion which wouldn’t be allowed in a more conventional historical account. Why? Because in the modern way of writing history, it is generally considered inappropriate to compare queens to lively young women of twenty-five. Can you imagine this sentence in a modern textbook about Elizabeth? The latter is the undermining of a queen, based primarily on the fact that she is a woman. Rather than compare her to other rulers in her family, especially those well-known for their sexual appetites, she is instead illustrated here as a frivolous young woman of the author’s imagining.

Recent Histories

First, we will look briefly at two sources from the twentieth century which showcase the changing tides of history from early Ranke to the Postmodern age. This will help you understand the current historical philosophy in a final source.

A World at War

Near the end of World War II, another Elizabethan biography was published, titled *Elizabeth and Leicester by Milton Waldman. This book, writtten before some major changes in historiographical philosophy after the war, is the most traditionally Rankean of all the sources we’ve discussed. It is exactly what most of us would consider ‘typical’.

Take the structure. Each chapter follows the lives of Dudley and Elizabeth in chronological order. There is a table of content and a list of illustrations at the beginning. Sources have been cited, and a thorough index is provided at the end for researchers. Most of the syntax, although telling a narrative, carefully avoids personal opinion, turning instead to primary and secondary quotations which underline the author’s point.

Finally, Elizabeth’s relationship with Dudley is focused mainly on public perception of the two, rather than individual conjecture by the author:

“And though she could not marry him, since he already had a wife, the scandal of the connection might make it impossible for her to marry elsewhere with advantage” (67).

Boring, right? It’s meant to be. To fully understand Rankean historiography, it’s best to read up on it separately.

A Postmodern Elizabeth

It was only during the postwar era of the 20th century that historians, again, made some major changes. The biography Gloriana: The Years of Elizabeth I by Mary M. Luke (1973) is one such example. Although it follows the regulated, approved structure the discipline had come to expect by this point, we can see the seeds of change.

First of all, you might notice this is the first biography written by a woman instead of a man. This is because history, as well as many other fields, were beginning to open their doors to outside voices for the first time. Second, the book is broken into themes like ‘The Coquette’, ‘The Pawn’, and ‘The Warrior’, following a more loosely chronological pattern.

There are, however, limitations to the changes from the previous source to this one. There are multiple reasons this might be the case, but most importantly is that the postmodern revolution did not make so much room for women that they could do whatever they wanted. To be taken seriously, it is likely that Luke had to adhere to a more conventional approach than white men within her field.

Where Does That Put Us Now?

The final biography, The Progresses, Pageants, and Entertainments of Queen Elizabeth I, is a compilation of essays written by many historians and edited primarily by Elizabeth Goldring. It is much more recent than the previous two, and indicates sweeping changes in the field of history since the source before it. This book was written after the postmodern ‘revolution’, which turned away from traditional historicism, and focused its attentions more on microhistories.

This book takes that interest to heart. It does not tell an overall account of Elizabeth I’s reign, in whatever style was more popular at the moment. Instead, this work sits in the realm of microhistory. It explans an often-overlooked facet of the Queen’s life, that of her processions from one estate to the next throughout England.

The book has several other elements more recognizable to the modern (or post-modern) reader. The first is simply that sources are consistently, rigorously listed in Chicago Style. Other things stand out, like an extensive list of contributors, three editors, and substantial use of images make a book most conventional historians would consider ‘good’ history. Here is where we can see the typical balance found between the extreme ideas of the postmodern era and the rigidity of the Rankean: a book that follows every ‘rule’ of Rankean history, while investigating a highly postmodern subject, written and edited almost entirely by women.

But what does a book of this nature, written mostly by women and very little about the conventional view of Elizabeth, have to say about her most popular love interest? Almost the same as the previous biographies:

“The attentiveness and proximity to the Queen of Robert Dudley, partly from his duties as Master of the Horse, led to scandalmongering about the real purpose of Elizabeth’s frequent progresses. In Ipswich, a citizen claimed that Elizabeth ‘looked like one lately come out of childbed’; about her progress in 1564, ‘Some say that she is pregnant and is going away to lie in.’ Another rumor asserted that ‘Lord Robert hath had fyve children by the Quene, and she never goeth in progress but to be delivered.’ Such rumors present an unsurprising slander of a Queen who loved travel, men, and power” (42-43).

However, this piece at least takes a less condescending approach: rather than comparing Elizabeth to a young, impressionable woman, these authors compare her to Kings. This is indicative of a writer who is both a woman, and a woman living in a world post second-wave feminism.

So what does this all mean?

There aren’t a lot of opportunities to understand how historians thought of women, because they didn’t write about us very much. The silence, in its own way, speaks volumes, in a way well represented by post-modernist feminist thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

However, by looking at a queen, especially a queen well loved by her people, too hard for men to ignore, we can start to understand an overal conceptualization of women in different eras. There are other ways of going about this, like looking at witches, fictional characters, and saints. That is our job, as modern historians: we have the responsibility to find the stories that were left out of history books, or barely included, and make sure those stories get told. The point of historiography, in this sense, is to think critically about the way we write these new stories, and understand not just what they say about the subject, but about us.

Works Cited

Archer, Jayne Elisabeth, Elizabeth Goldring, and Sarah Knight. The Progresses, Pageants, and Entertainments of Queen Elizabeth I. Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2007. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=430310.

Author of The history of England. Observations and Remarks upon the Lives and Reigns of King Henry VIII. King Edward VI. Queen Mary I. Queen Elizabeth, and King James I. With Particular Characters, after the Earl of Clarendon’s Method, of All Their Favourites; and the Most Eminent and Illustrious Persons Both in Church and State, That Flourish’d in England during Those Reigns. Collected from Publick Histories and Private Memoirs. By the Author of The History of England in 2 Vol. 8vo.

London: Printed for James Knapton in St. Paul’s Church-Yard; Ratph Smith under the Royal Exchange; William Taylor in Pater Noster Row; Hammond Banks at the Golden-Key in Fleetstreet, and C. King in Westminster-Hall, 1712. http://tinyurl.gale.com/tinyurl/C7t3y2.

Luke, Mary M. Gloriana: The Years of Elizabeth I. New York, NY: Coward, McCann & Geighegan, Inc., 1973.

Neale, J.E., and J E Neale. Queen Elizabeth I. Chicago, UNITED STATES: Chicago Review Press, 2005. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unm/detail.action?docID=1784981.

Neale, John Ernest. Queen Elizabeth,. First edition. New York, [c1934]. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015014499092.

Pflug, Günther. “The Development of Historical Method in the Eighteenth Century [1954].” History and Theory 11 (1971): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2504244. Waldman, Milton. Elizabeth and Leicester. London, UK: Collins, 1944.

3091 words. /essays/thematic/women-gender/historiography-of-elizabethi.html